-

G Allen: Changing Games and Changing Lives

By Chase Hartsell

G Allen (pictured center) emerges from the dugout as starting lineups are announced at Ouachita’s Rab Rodgers Field in Arkadelphia. | Photo: Caity Hatchett/Baseline Photography Ouachita Tiger outfielder G Allen stands in front of his bathroom mirror. In just a few hours, the triumphant horns in NEEDTOBREATHE’s “MONEY & FAME” will announce Allen’s arrival at home plate. He will step into the left-handed batter’s box, looking for a pitch that he can give a ride off of the barrel of his bat. Perhaps he will tally another home run to raise a career total that has already swelled above 30. He could also walk or single, giving him the chance to add to his nearly 30 career stolen bases. Regardless, Allen possesses the ability to change the game with one swing. Right now, however, his eyes are fixated on a picture placed in front of him. It’s a picture he’s had since high school, and it features a quote from Super Bowl champion football coach Tony Dungy. “God’s definition of success is really one of the significant differences our lives can make in the lives of others.”

*****

A native of Little Rock, Arkansas, G Allen received an early introduction to the game of baseball.

“Pretty much ever since I could walk, I think I was doing something with a ball,” Allen said. “I always loved hitting. I remember being five or six in the backyard – hitting off of the tee with the plastic bats and wiffle balls. I just fell in love with it.”

G’s father, Will Allen, competed on Little Rock Central High School’s football and baseball teams before playing college football at the Division I level. Though he chose the gridiron over the baseball diamond for his own collegiate career, Will played a large part in fostering his son’s love for America’s pastime.

“It was just one of those things of going out into the yard and playing catch, or him just pitching to me in the backyard, coaching my teams [and] being a part of my teams,” G said of his relationship with his father. “He was definitely a big influence and got me into the game.”

Inside the Allen household, the family television provided G with his first glimpse of his favorite Major League Baseball team: the Atlanta Braves. His favorite player was Hall of Fame third baseman Chipper Jones.

“When Chipper Jones would come up to bat, I would do his stance and take pitches with him on the TV,” Allen said. “That’s what inspired me to play third base. I switch-hit [like Chipper] when I was younger, too.”

During his senior year of high school, Allen got the chance to meet his childhood hero during a USA Baseball camp at IMG Academy in Bradenton, Florida.

“He was actually putting balls on the tee for me one day, and I was just hitting,” Allen remembered. “That was super cool.”

G attended high school at Little Rock Christian Academy (LRCA): a place that impacted him greatly in multiple areas of his life.

“It was a ground for growing spiritually,” Allen said of LRCA. “I think that really prepared me for college and the tough times I’ve been through where my faith has been what got me through.”

*****

As his high school days neared their end, Allen decided to continue his playing career with the Texas Christian University (TCU) Horned Frogs in Fort Worth, Texas.

“When you’re in high school and you start getting offers and looked at, you start making a list of schools you want to go to,” Allen explained. “TCU was on that list for me. I just loved the campus; loved the whole recruiting style [and] what they had to offer. It was a smaller school that was closer to home, but also really good at baseball. [I] met some great people there.”

One of these people was Luke Savage: a Horned Frog pitcher and G’s roommate at TCU. The two quickly became close friends, leading Savage to introduce Allen to one of his passion projects.

Blessed Feet is a non-profit rooted in the Bible verse found in Romans 10:15, which reads, “As it is written, ‘How beautiful are the feet of those who bring the good news.’” The organization was inspired, in large part, by Savage’s mission trips to the Dominican Republic with his Prestonwood Christian Academy baseball team from Plano, Texas. On these trips, Prestonwood conducted ministry work while also playing baseball with local children. During the games, Savage noticed that the children were either wearing extremely worn shoes and cleats or nothing at all. This realization inspired him to take action by, as Allen put it, “help[ing] kids out and help[ing] communities in need by giving them shoes, but also meeting their needs in other ways.” When the TCU pitcher officially started the non-profit during his early college days, he invited G to become a member of the board.

“Ever since freshman year, we’ve had two trips down to the Dominican Republic where we’ve been able to hand out hundreds, if not thousands of shoes while also sharing the Gospel,” Allen said. “We’ve also been able to help out in other ways around the community, and we’re hoping to expand that more as the years progress and we get more funds.”

While G experienced positivity from his involvement in the non-profit, that sensation often failed to carry over to his work on the baseball diamond with the Horned Frogs.

“It got to the point where I just did not enjoy playing baseball,” Allen said. “I didn’t like showing up to the field [and] had a lot of anxiety about playing and performance – things like that. I just told my parents, ‘I don’t think I can do this anymore.’”

*****

Having recently experienced a call to ministry, Allen considered leaving baseball behind and simply pursuing a degree at Christian university. Around this time, Allen’s best friend and teammate from high school, Isaac Nowell, committed to play as an outfielder at Ouachita Baptist University (OBU).

“As I was talking to [Isaac], he was like, ‘You should totally come to OBU and play,’” Allen said. “I can say it was a really hard decision in the moment [to leave TCU], because that was my dream and what I’d worked for.”

In the end, however, Allen did decide to leave the Horned Frogs and join his best friend as a part of the Ouachita Tiger baseball team. Looking back on the decision, he has no regrets.

“First and foremost, I think it was the Lord’s hand in all of it,” Allen said. “Coming to OBU has been amazing. It’s been such a blessing and such a fruitful time here – not only on the field, but off it as well.”

For Allen, one of the greatest fruits of being a Tiger is the opportunity to reconnect with Isaac Nowell as a teammate and a friend.

“Getting to have that friendship and someone you can play with – someone you can goof around with on the field but also somebody that, when we go home for breaks, I can work with and just get better at the game with – it’s been a blast.”

On top of connecting with his old friend and new teammates, Allen has connected with the ball itself at a stellar rate. As of this writing, the Little Rock native has 36 career home runs, putting him in second place on Ouachita’s all-time list for that category. He also has at least 13 stolen bases in both of the last two seasons. Despite moving from his lifelong position of third base to left field in the middle of the 2023 season, Allen earned an All-American selection from the Division II Conference Commissioners Association as one of the nation’s top outfielders.

While Allen’s athletic determination is on full display at the Tigers’ home of Rab Rodgers Field, the left fielder’s internal drive does not stop at the door of his team’s dugout. In fact, G’s competitive spirit on the field may only be matched (if not exceeded) by his motivation in the classroom. The same year that he earned athletic All-America honors, Allen was named a College Sports Communicators First-Team Academic All-American and Ouachita’s Male Scholar Athlete of the Year. This emphasis on academics can be traced back to early encouragement from G’s parents.

“I think they knew the potential I had – not only athletically, but intellectually – to succeed,” Allen said.

The Allens’ belief translated to their son, who seeks to give his best effort in all of his studies.

“I’m somewhat type A in that regard – I’m a perfectionist – so not settling for what I know I can do better than [is important],” G said.

Allen is a philosophy major studying in Ouachita’s Pruet School of Christian Studies. Much like his teammates at Rab Rodgers Field, he believes that his classmates push him to constantly better himself.

“You want to compete with your friends,” Allen explained. “If you’re surrounding yourself with people who are, in general, pretty good students, you want to compete with them and be a good student as well.”

*****

Now in his senior season at Ouachita, G Allen will soon patrol left field at Rad Rodgers Field for the final time. The horns of “MONEY & FAME” will blare for the last time as the senior assumes his position in the left-handed batter’s box. When that plate appearance arrives, Allen will look to give the fans and his teammates one more memorable moment – whether it be a home run, a stolen base, or another result entirely. When he exits the diamond for the final time, though, the All-American hopes that the Tigers will remember him for more than just his highlight reel.

“Yes, I want to be remembered for being a great player and playing hard – maybe breaking a record or two,” Allen said. “But more importantly, I want the teammates that I’ve played with – who have graduated and teammates that are going to still be here when I leave – to look to an impact I made on them or the way I made them a better person. I think that’s probably what I want to be remembered for: someone who made an impact in others’ lives.”

-

In Harms’ Way: The Journey of Ouachita QB Riley Harms

By Chase Hartsell

Ouachita quarterback Riley Harms zones in on the field ahead as he scrambles with the football. | Photo: Ouachita Athletics To reach Ouachita Baptist University from the city of Fremont, Nebraska, one must travel approximately 707 miles. For Tiger quarterback Riley Harms, those 707 miles have held a fair share of roadblocks – and they are not the typical traffic lights or construction zones. Despite these setbacks, the Fremont native locks his eyes on the road ahead. His trip is not fueled by ethanol or electric charge. Instead, Harms presses on with the aid of football, family, and faith.

Like many young men his age, Harms found himself drawn to football by the example of seven-time Super Bowl champion Tom Brady.

“Growing up watching him be as passionate as he was and loving it as much as he was for as long as he did – he’s definitely who drew me to the game,” Harms said of Brady. “Tom Brady is somebody that I consider a mentor, even though I’ve never met him.”

Following in his hero’s footsteps, Harms played quarterback throughout his childhood. As a sophomore at Fremont High School, Harms received the opportunity to start four varsity games after the previous starting quarterback suffered a season-ending injury.

“We won all four of the games; we were 1-5 before that,” Harms remembered. “It showed that it wasn’t just a fluke – that I was capable of doing well, even as a sophomore.”

After his sophomore year, Harms experienced a growth spurt that changed the trajectory of his athletic career.

“Somewhere between my sophomore and junior year of high school – when I started to grow into my body a little bit – is when I knew that I could be better than I had ever thought before that.”

In three seasons with Fremont High School, Harms set new program records for touchdown passes and completion percentage in a season and a career. His work on the field caught the eye of college coaches, including Nebraska-Kearney quarterbacks coach Kevin Bleil.

“I had a really good relationship with [Coach Bleil],” Harms said. “He watched me play all my sports, and he and I were very like-minded about how offensive football should look.”

After an enjoyable official visit to campus, Harms decided to play for Coach Bleil and the Lopers. Following the end of the 2018 season, though, Bleil left the program to take a job at Stephen F. Austin. Not wanting to give up on his new team, Harms did his best to adapt to new offensive coordinator Drew Thatcher’s gameplan. When he suffered an injury and struggled to adjust to Kearney’s new triple-option setup, however, the quarterback felt that the writing was on the wall.

“It just really didn’t fit my style anymore, and I felt that I needed to give myself a better opportunity to play,” Harms said.

When Harms voiced his desire to find a new college home, wide receivers coach Augustine Ume-Ezeoke suggested his own alma mater: Ouachita Baptist University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. The former Second Team All-GAC linebacker connected Harms with Tiger head coach Todd Knight.

“I came on a visit, and I knew it was the right place for me right away,” Harms said.

Though the 2020 season was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fremont native earned his spot as Ouachita’s starting quarterback heading into 2021. But before Harms could realize his dream of leading a college offense, he suffered another injury ahead of the Tigers’ 2022 campaign and found himself issued a medical redshirt. His first season as a first-string college quarterback was over before it could even begin.

“You finally feel like, ‘I’ve got my opportunity,’” Harms explained. “Then for it to just be taken away from you in an instant: that was really, really hard.”

While recovering from injury, Harms experienced a turning point in his faith while working as a camera operator at the Super Summer Arkansas camp on Ouachita’s campus.

“I just felt like it was really time for me to take the next step,” Harms said. “I talked to the guy that was running the camp, Warren Gassaway, and he helped me take the next step in my faith and really just proclaim my faith in God and Jesus.”

According to Harms, faith has played a vital role in his response to adversity.

“My faith has definitely helped me see that there is a reason for everything,” the Tiger quarterback said. “No matter what happens in life, you have to find a way to turn it into a positive. If nothing else, it’s made me a lot tougher.”

On top of his faith, Harms finds support in the presence of loved ones, such as fiance Maegan Holt. A two-time all-conference selection with Nebraska-Kearney’s women’s basketball team herself, Holt can empathize with the ups and downs of Harms’ journey as a student-athlete.

“She understands the grind,” Harms said. “I don’t know that I’d have been able to get through all of this without her being in my corner.”

Holt isn’t the only one in Harms’ corner: the quarterback’s family makes the trip from Nebraska for nearly every Tiger football game. This includes Harms’ grandma, who is currently battling brain cancer.

“To see how she has fought through that and how she’s able to make a trip 10 hours away to watch me play football is pretty amazing, right?” Harms said of his grandma. “It’s something that I can draw inspiration from, because she never lets it bother her.”

Strengthened by his faith and family, Harms endured the injury rehabilitation process to reclaim his starting quarterback position for the 2022 season. In his first season as a college starter, he led the Tigers to an undefeated regular season and Great American Conference title. The following year, while battling injury once again, he threw for a Ouachita-record 22 touchdown passes. Though Harms didn’t initially realize that he had the record, it didn’t take long for the weight of the achievement to set in on the quarterback.

“There’s a lot of stories here,” he said of the Tiger football program. “There’s been a lot of really good quarterbacks: Kiehl Frazier, [Austin] Warford, Brayden Brazeal. The fact that I threw for more [touchdowns] than any of those guys is surprising.”

What might surprise others just as much is Harms’ decision to return to Ouachita for the team’s 2024 campaign. Though his college career started in 2018 and he has faced multiple severe injuries, the Tiger graduate student felt that coming back to play one last season while finishing his Master of Science in Exercise Science was a no-brainer decision.

“It’s just my true love,” Harms said of football. “It’s my passion. I consider myself so lucky to have ever been able to play it. For me, to not exhaust every ounce of this opportunity that I get feels like it would be a waste.”

In spite of everything that he has experienced and achieved, the Nebraska native’s eyes remain fixed on the future. Having already traversed the 707 miles between his original home of Fremont and his newfound home of Arkadelphia, he is yet to reach his final destination. Caution to those standing in Harms’ way: he is showing no signs of slowing anytime soon.

-

Sarah Dean and Meghann Bledsoe are a picture-perfect team as Photo Lab editors

By Chase Hartsell

Meghan Bledsoe (pictured left) and Sarah Dean (pictured left) briefly step out from behind the camera to take a photo during Battle of the Ravine. Bledsoe and Dean are Ouachita’s Photo Lab editors for the 2023-2024 school year. | Photo: Sarah Dean If you’ve recently picked up a copy of The OBU Signal, read an article on Ouachita’s website, or reminisced on last year’s events with The 2023 Ouachitonian, then chances are you’ve encountered the work of Sarah Dean and Meghann Bledsoe. Dean and Bledsoe are co-editors of the Ouachita Photo Lab for the 2023-2024 school year. For both women, the role represents the latest step in an ongoing photography journey.

Dean, a senior from Nashville, Tenneseee, developed an interest in photography at an early age through traveling with her family.

“We took a lot of really expansive road trips,” Dean explained. “I would use my parents’ phone, or when I got a phone or iPod, I started just using the camera on those and taking pictures. We went to some pretty cool places, so I loved documenting that and taking creative photos.”

During her high school years, Dean received her own camera as a Christmas gift. From there, the Tennessean began to seek out opportunities that would provide practical experience and help her decide if she wanted to delve deeper into photography.

“Through[out] high school, I took photos on vacations,” Dean said. “I took pictures for a couple that got engaged in [my family’s] church, and that was sort of the first time that I [did] portraiture work. When I got into college, I knew that I wanted to pursue photography full time, so I got involved with Photo Lab.”

Born in China, Sarah was adopted alongside her sister, Lydia (Class of 2022), when she was just ten months old. In spite of her life’s uncertain start, the senior has no doubt that she is right where she is meant to be.

“It’s just been really cool throughout my life to know that God had a specific family that I belonged to,” said Dean. “We’re a really close, tight-knit family, and that’s contributed to who I am today. My parents have always stood behind me, supported me, and encouraged me in pursuing what I have a passion for.”

Sarah Dean breaks for a picture with her camera on the sideline at Cliff Harris Stadium. Dean says that Tiger football and baseball games are amongst her favorite Ouachita events to cover. | Photo: Sarah Dean Meghann Bledsoe, a junior from Plano, Texas, also began her photography journey with the gift of a camera. Unlike Dean, however, she did not initially plan to take still photos.

“Growing up, I really liked making YouTube videos,” Bledsoe said. “That was my little hobby. I really wanted a nice camera to make better videos. One year, my dad spontaneously got me a camera. As I started playing around with it, I realized, ‘Oh, it has a photo setting.’”

This chance discovery led the junior to experiment with photography.

“I would play with the setting, and take pictures of my dogs, my cousins, and my siblings,” Bledsoe remembered. “That kind of sparked [my passion]. I just found it so fascinating.”

People continue to be a primary motivator in Bledsoe’s work. Her mother and father are both deaf: a situation that taught their daughter the value of visual storytelling from an early age. Though she herself does not suffer from impaired hearing, the Texas native primarily communicates with her parents through American Sign Language. According to Bledsoe, the sight-based medium of photography provides a unique point of connection with her family.

“I think [photography is] special because I view photos as a part of storytelling,” Bledsoe said. “I feel like it’s very inclusive, and it can bring my parents into [a place] where it can start a conversation.”

When Bledsoe arrived as a second-semester freshman in the spring of 2022, her family’s story quickly caught the attention of Ouachita’s yearbook team. During a Ouachitonian photo shoot, she met Levi Dade (Class of 2023), who was a Photo Lab editor at the time.

“Levi was taking photos of me, and I asked him about his camera because I was really curious,” Bledsoe recalled. “We started talking about photography, and he was like, ‘Oh, Meagan, you should get involved [in Photo Lab]. We have opportunities here for you to use your skills and show off your work.’”

Meghann Bledsoe poses for a photo that was included in The 2022 Ouachitonian. During this photoshoot, Photo Lab editor Levi Dade suggested that the Texas native join Ouachita’s photography program. | Photo: Levi Dade Though she didn’t join Photo Lab immediately, Bledsoe was consistently encouraged by the work and support of Dade and fellow Photo Lab editor Abby Blankenship (Class of 2022). After taking photos of events such as Tiger Serve Day as a volunteer in 2022, the Plano resident did not look back. As she continued to serve and rose into a leadership position of her own in Photo Lab, Bledsoe often looked to the veteran Dean for inspiration.

“She’s awesome,” Bledsoe said of Dean. “I feel like I’ve learned so much from her. She definitely sets a high standard of quality work. Watching her – it’s encouraged me to work harder and grow in my photo-taking skills.”

Dean echoes respect for her co-editor.

“I love working with Meghann,” Dean said. “Communication has been awesome, and it’s been really fun just getting to know her better. We work really well together.”

Since August, Bledsoe and Dean have captured images of a wide variety of Ouachita offerings, including Welcome to Ouachita’s World (WOW), stage and music productions, and Tiger athletic events. In one of their more interesting tests of the fall semester, the duo managed to take photos of Tiger Tunes while also performing in the show.

“That was a fun challenge,” Dean said of her experience. “I was running around, and it was pretty hectic, but it was fun. I got to see all of the shows several times, and [I] got to take pictures and [preserve] them for the school’s memories. It was just really cool to be a part of that.”

As their participation in Tunes suggests, the Photo Lab editors’ influence within the Ouachita community is not limited to their spots behind the camera. Dean is actively involved in her social club, the Women of Chi Mu, and she currently serves as the group’s social media chair. In December 2023, the university announced Dean as one of 33 seniors featured in the 2024 edition of Who’s Who Among Students at Ouachita.

Bledsoe is a leader for Ouachita’s Campus Ministries, where she works with an emphasis on missions. She is also an active member in the Women of Tri Chi social club.

Wrapping up the first semester as co-editors of the program, both women acknowledged the growth and new opportunities they have enjoyed in their time with Photo Lab.

“I can see through the years – as I took more photos and covered more events that exposed me to different situations – how much I grew as a photographer,” Dean said.

“It’s a really great way to connect with people,” Bledsoe said of Photo Lab. “One of the great things about getting to shoot [pictures] on campus is the amount of people I get to see from all different spheres of Ouachita that I probably wouldn’t have [have experienced] myself.”

Dean and Bledsoe will continue to lead Photo Lab through the spring semester, but if the adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” is true, the duo has already gifted the Ouachita community millions.

-

The Wonder from Waldo: Travis Jackson

By Chase Hartsell

The following article is part three of a series titled “Hidden Heroes: An Arkansas Sports Anthology.” The state of Arkansas has a rich athletic history and, as such, has plenty of sports stories to tell. As a result of this plethora, however, some stories have slipped through the cracks. “Hidden Heroes” sheds light on lesser-known, yet valuable sports tales from the Natural State that have received limited coverage either in their own time or in the present day. Furthermore, the series aims to go beneath the surface of featured athletic stories to uncover universal themes and truths that transcend both time and sport. Click here to read part one, which covers Jim and Leander Tugerson’s push for integration with the Hot Springs Bathers in 1953. To learn more about Bill Walton, a Benton native who served as Bear Bryant’s first head football coach at Fordyce, click here for part two of the series.

A baseball autographed by Travis Jackson sits on a fireplace mantel. | Photo: Chase Hartsell On December 3, the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Veterans Committee will announce its voting results for the Hall of Fame Class of 2024. For those bypassed by the Baseball Writers Association of America’s original ballot, this vote represents another opportunity to join baseball’s most elite group in Cooperstown, New York.

As of the time of this writing, seven National Baseball Hall of Fame members were born or grew up in the state of Arkansas. This group features generational talents such as eight-time stolen base champion Lou Brock (El Dorado), 16-time Golden Glove winner Brooks Robinson (Little Rock), ten-time All-Star infielder George Kell (Swifton), 1934 National League MVP Dizzy Dean (Lucas), and 1935 batting champion Arky Vaughan (Clifty). It also includes New York Yankees catcher Bill Dickey, who grew up in Kensett and Searcy, Arkansas. Dickey, one of the namesakes of the Arkansas Travelers’ Dickey-Stephens Park in North Little Rock, won eight World Series titles while playing alongside Yankee legends such as Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. As his career reached its prime in the 1930s, though, another native Arkansan found himself putting the finishing touches on his own Hall of Fame career on the other side of the Big Apple’s Harlem River.

Travis Jackson, born in Waldo, Arkansas, was an infielder for the New York Giants (now the San Francisco Giants) from 1922 to 1936. A one-time All-Star and one-time World Series champion that never led the major leagues in any offensive category, he seemed an unconventional Hall of Fame selection to some. Fortunately for Jackson, his life and career made sure that he was familiar with unconventionality.

Small-Town Start

Travis Jackson’s life began in Waldo on November 2, 1903. The Central Arkansas Library System’s Encyclopedia of Arkansas writes that, although Waldo’s population never exceeded 1,000 residents during Travis’ youth, the town thrived due to the local railroad and lumber industry throughout the early 1900s. It served as the perfect host for the young Jackson family, which included father William, mother Etta, and only child Travis. According to Society of American Baseball Research (SABR) writer Greg Erion, “early news clippings suggest that Travis’ parents named him in honor of William Barrett Travis, hero of the Alamo.”

While William stayed busy with his career as a wholesale grocer, it did not stop him from spending quality time with his son. In a 1930 Sporting News article, Travis credited his father for introducing him to baseball.

“[Dad] bought me a hardball when I was three years old, and he used to sit in a rocker on the front porch while I sat on the grass in the yard and we’d play catch by the hour,” Jackson told the reporter.

Young Travis continued to hone his skills as a ballplayer and, according to a 1982 United Press International (UPI) article, he joined the ranks of semiprofessional baseball through a local team at age 15. Just one year prior, Jackson had an encounter that would change the trajectory of his life and baseball career.

Multiple sources report that, at age 14, Travis Jackson got to meet Little Rock Travelers manager Kid Elberfield. The Travelers (known today as the Arkansas Travelers, the Double-A affiliate of the Seattle Mariners) were a minor league baseball team with membership in the Double-A Southern Association. Jackson later told Finos Johnson of UPI that his uncle, who owned a drugstore in Little Rock, introduced him to the Travelers’ manager. Following a short, persuasive pitch from Travis’ uncle, Erion writes that Elberfield offered the 14-year-old Jackson a chance to show off his skills. The young ballplayer took the opportunity and conducted an impromptu showcase. The display evidently impressed Elberfield because, as Erion mentions, the minor league coach “asked [Travis] to promise that in a few years he would contact Elberfield.” After finishing high school, Jackson fulfilled this promise when he signed with the Travelers in 1921.

“They called me before I had the chance to call them when I got out of high school,” Jackson said of the Travelers in his interview with Johnson. “[Elberfield] must have seen something he liked in me.”

Next to a postcard of Travis Jackson’s Hall of Fame plaque, a pushpin identifies the location of Waldo on an Arkansas highway map. Jackson was born in Waldo, and he also began his baseball journey there when he started playing catch with his father at three years old. | Photo: Chase Hartsell Professional Baseball Breakthrough and College

Located mere feet from the future location of Little Rock’s Central High School (where, in 1957, the Little Rock Nine famously made their push for integration), Kavanaugh Field, the home of the Little Rock Travelers, proved to be a valuable learning ground for Jackson. Playing in 39 games for the Travelers in 1921, the young shortstop showed flashes of brilliance amidst struggles at the plate and in the field (.200 batting average and 21 fielding errors). The following season, Jackson played in 147 games for Little Rock. Though his batting improved significantly (.280 batting average in 1922), his defense still served as a cause for concern (including a Southern Association-worst 73 errors). Nonetheless, Kid Elberfield recommended Jackson to New York Giants manager John McGraw, who was fresh off a 1921 World Series championship campaign. McGraw bought Jackson’s contract on June 30, 1922, on the condition that he would play out the remainder of the minor league season in Little Rock.

A rare photo of Kavanaugh Field showcases a sold-out crowd at the stadium that served as the Little Rock Travelers’ home for more than three decades. Located mere feet from the current site of Little Rock Central High School, the site currently houses the school’s football field: Quigley Stadium. | Photo: Arkansas-Democrat Gazette/Jack Schnedler According to his Baseball-Reference page, Travis Jackson made his major league debut with Giants on September 27, 1922, in a late-season home game at the Polo Grounds. He had yet to turn 19 years old. Though the young shortstop failed to record his first hit in two at-bats, New York narrowly defeated the Philadelphia Phillies 3-2. Jackson appeared in two more games during the regular season, with these serving as his last appearances on the field in 1922. The Giants ended the year with a second consecutive world championship, though Jackson did not record enough playing time to earn credit for the title.

To begin the 1923 season, the New York Giants named future Hall of Famer Dave Bancroft their starting shortstop. The decision made sense: just one season earlier, the veteran led the league in games played (156) while having a career season at the plate (209 hits on the year). Greg Erion writes that “once play began [the next year], however, Bancroft started to experience leg pains” and eventually developed “a case of influenza that took him out of the lineup for six weeks.” In the meantime, Jackson took over at shortstop and “showed McGraw he was ready to handle the position” by recording a .275 batting average and providing solid defense in 96 games in 1923. After the Giants’ season ended with a World Series loss at the hands of the Yankees, John McGraw made the decision to send Bancroft to the Boston Braves. At just 20 years old, Travis Jackson was a starting shortstop in the major leagues.

Around the time of his start in professional baseball, Jackson enrolled in classes at Ouachita Baptist College (now Ouachita Baptist University) in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, though it remains unclear as to whether or not he ever played for the school. Multiple sources, including Encyclopedia of Arkansas, suggest that he at least “played for a team at Ouachita” during his teenage years. Jackson’s New York Times obituary even claims that Jackson “starred on the Ouachita College team before turning professional.” SABR’s Erion, though, simply states that, after finishing high school, Jackson “joined the [Travelers], at the same time enrolling at Ouachita Baptist College.”

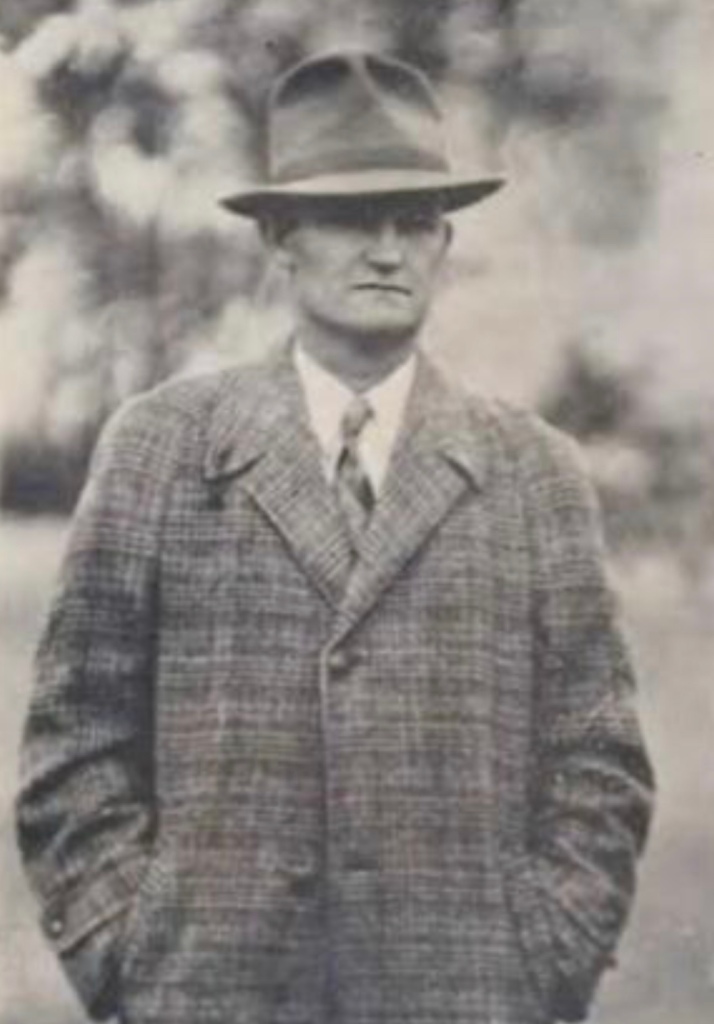

Travis Jackson (pictured) is featured in a college portrait in the 1924 edition of the Ouachitonian yearbook. School records indicate that Jackson studied at Ouachita from 1921 to 1925 and, as the quote above implies, garnered respect from many of his classmates. | Image: The 1924 Ouachitonian Regardless of his official playing status at Ouachita, Jackson left a mark on his collegiate alma mater. The 1922 edition of the Ouachitonian yearbook reveals that he was the president of his freshman class. In 1923, the Ouachitonian praised the Waldo native for involvement in various fine arts programs. The school’s yearly publication described him as “a real jack-of-all-trades” who “played the hero in ‘Peg o’ My Heart,’ shortstop for the Little Rock Travelers, drums in the ‘jazz’ orchestra, the Manly Duke in the ‘Vodville,’ and havoc with the ladies’ hearts. Certainly some man!” Respect for Jackson continued to grow during his junior year, with 1924’s Ouachitonian describing him as “not only a New York Giant, but a giant in heart and spirit.” Ouachita Baptist University’s records show Jackson as a former student last enrolled in 1925.

More than 80 years after he left Ouachita, the athletic department elected Jackson to its Tiger Athletic Hall of Fame. This group, including Jackson, is honored with a portrait wall inside the university’s Sturgis Physical Education Center (also known as SPEC).

Travis Jackson’s photo greets guests near the entrance Ouachita’s Sturgis Physical Education Center. The university installed the portrait to celebrate Jackson’s induction into the Tiger Athletic Hall of Fame in 2008. | Photo: Chase Hartsell The Rise of “Stonewall”

In 1924, Travis Jackson got his first true taste of a full season at the major league level. He appeared in a career-high 151 games and batted over .300 (.302) for the first time in his career while helping his team win the National League for the fourth year in a row (the Giants once again fell short of a World Series title). The young shortstop continued to develop his plate discipline over the next few seasons, allowing him to retire with an excellent 8.5 percent strikeout rate (for reference, the average MLB strikeout rate in 2021, according to Baseball America, was 24 percent). All the while, Jackson continued to improve in the field, and he soon garnered a reputation as one of the best defensive shortstops in baseball. It was “his ability to stop balls from going through the infield,” Greg Erion writes, that earned him the nickname “Stonewall” (after Civil War General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson).

“In all the years I watched him, playing with him and against him, I never saw him make a mistake,” two-time MVP and fellow Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby once said of Jackson.

Though Hornsby spent only one season with the Giants before departing to play for the Boston Braves in 1928, his comment on Jackson took on even greater weight when, as the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2023 Yearbook points out, the Waldo native succeeded him as New York’s team captain.

The late 1920s presented Jackson with new highs both in his career and his personal life. In 1927, despite undergoing an appendectomy at the start of the season, he batted .327 with 14 home runs and 98 runs batted en route to a fifth place finish in National League MVP voting. The following offseason, he married his hometown sweetheart, Mary, before posting another top 10 finish in NL MVP race in 1928. A year later, he homered a career-best 21 times and drove in 94 runs before welcoming his first child, William, in October 1929. As a newly minted father in 1930, Jackson recorded career bests in batting average (.339) and on-base percentage (.386).

Throughout his professional career, Travis maintained strong ties with his home state of Arkansas. In addition to establishing Waldo as his offseason home, Jackson, according to a plaque commissioned by the Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail in Hot Springs, Arkansas, participated in the city’s rich spring training tradition with the New York Giants. Furthermore, local records and scorecards reveal that Jackson’s Giants played multiple exhibitions in other Natural State cities such as El Dorado and Pine Bluff (with these games often pitting New York against the Cleveland Indians, now known as the Cleveland Guardians).

Travis Jackson, donning his Giants uniform, is shown practicing his defensive skills. The Arkansan’s glove earned the respect of many teammates and opponents, including Giant captain and fellow Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby. | Photo: The Sporting Blog Adversity, Resurgence, and a Strong Farewell

As the 1931 season passed, Jackson continued to produce at a solid rate as he once again finished in top 10 (seventh) in MVP voting. During his 1932 campaign, however, his health forced him to endure a number of setbacks. In addition to continued knee pain (which, it turned out, was the result of bone chips that required surgery), Erion claims that Jackson suffered from a bout with influenza. These ailments limited the shortstop to just 52 games that season, and the Giants fell short of the NL pennant for an eighth consecutive season.

Though Jackson’s ailments limited him to just 53 regular season games in 1933, he managed to help his team claim its first National League pennant since 1924. During his first World Series in nearly a decade, “Stonewall” stepped up with four hits and two runs batted in as the Giants won the world title over the Washington Senators in just five games.

On the heels of a World Series triumph, Jackson experienced a personal resurgence in 1934 while appearing in 137 games (his most since 1931 and the fifth-highest total of his career). He received his first and only All-Star selection when the National League named him its starting shortstop for the second-ever All-Star Game. When the Waldo native exited the game after two at-bats, fellow Arkansan and Hall of Fame member Arky Vaughan took his place. Jackson finished the season with a .268 batting average (his highest since 1931), 16 home runs, and a career-best 101 runs batted in. At the end of the season, he placed fourth in the National League’s MVP vote: the highest finish of his career.

One year later, Jackson finished with a batting average above .300 (.301) for the sixth and final time. He retired from full-time play after appearing in 126 games in 1936, but not before he helped the Giants claim one last NL pennant and World Series appearance. Jackson and his teammates lost the series in six games to that year’s New York Yankees squad, which featured Bill Dickey at catcher.

“I’m glad to say that I went out on a big league club and in the World Series,” Jackson later said.

Travis Jackson takes a big swing from the right-handed batter’s box. Though most contemporaries knew him for his glove, he also batted .300 or better in six different seasons during his Hall of Fame career. | Photo: National Baseball Hall of Fame From the Batter’s Box to the Coach’s Box and Retirement

In his biography of Jackson, Erion states that the Waldo native was set to serve as a player-manager for the Jersey City Giants (double-A affiliate of the New York Giants) starting in 1937. Due to nagging knee issues, he played in only 16 games between the 1937 and 1938 seasons. Jackson left the team midway through its 1938 campaign, though he stayed a coach in the Giants’ system until 1940. That season, he experienced a tuberculosis scare that, according to Arkansas-Democrat Gazette writer Rex Nelson, left him in a sanitarium for six years. After completing his recovery, the former Giant returned to a coaching role with New York. Jackson continued to work for the Giants until the conclusion of the 1948 season, when the team released him. From there, he served as a manager in the minor leagues for the Braves until his retirement following the 1960 season.

As he wrapped up his career in baseball, Jackson received the news of his selection to the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame’s 1960 class. To his thrill, he was inducted within one year of Bill Dickey.

“Now that was another great one to be there with,” Jackson said of Dickey, who also started his professional baseball career with the Little Rock Travelers.

After his career in baseball ended, Jackson returned to Waldo where, as the United Press International article states, he lived with his wife “in a white frame house about a block north of his family’s original home.” During his retirement, he enjoyed the company of friends and family, including six grandchildren.

The Call to the Hall

Six decades after his major league debut, Travis Jackson received the call to Cooperstown as one of four inductees in the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s 1982 class. His classmates included all-time home run king Henry “Hank” Aaron, two-time MVP and World Series champion Frank Robinson, and former Major League Baseball Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler. While Aaron and Robinson earned induction from the standard ballot conducted by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, Jackson and Chandler received their selections from the Hall’s Veterans Committee. For Jackson, the call from the Hall of Fame was a welcome surprise.

“[The Veterans Committee] mentioned four or five people that were eligible for [induction], and my name wasn’t even on [the list],” he explained to writer Finos Johnson. “I was selected and they didn’t even select the ones in the paper.”

(Pictured left to right) Travis Jackson, A.B. “Happy” Chandler, Frank Robinson, and Henry “Hank” Aaron hold framed images of their respective Hall of Fame plaques. The National Baseball Hall of Fame officially inducted the group into its ranks on August 1, 1982. | Photo: National Baseball Hall of Fame Regardless, the former New York Giant found himself in Cooperstown, New York, for the National Baseball Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony on August 1, 1982. As Jackson stood behind the podium in front of thousands of fans on that sunny day, a graphic on the television broadcast proudly proclaimed that “this [was] his first visit to Cooperstown.”

To begin his six-minute induction speech, Jackson took a full minute to introduce his friends and family from the Arkansas communities of El Dorado, Texarkana, and Waldo. From there, the newest Hall of Fame member used the next two minutes to tip his cap to former teammates and coaches as well as the young fans in attendance. Finally, at the halfway point of his address, Jackson turned his attention to his own career by addressing the question of what he considered to be the biggest thrill of his baseball career. He told the crowd about how that decisive moment had started as his first time walking into a professional baseball stadium in Little Rock and how, over time, it evolved into the ceremony that day. All the while, Jackson made sure to give props to individuals who helped him in his journey, including his opponents. Once his story reached its full circle by returning back to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the former New York Giant ended his speech by simply telling the audience, “Ladies and gentlemen… that’s it.” He received a standing ovation as he returned to his seat.

A Memory Preserved

Nearly five years after the ceremony, Travis Jackson died from complications of Alzheimer’s disease in his hometown of Waldo on July 27, 1987. He was buried in the town’s Waldo Cemetery.

This month, November, is Alzheimer’s Awareness Month. According to the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America, more than 6.2 million Americans are battling the disease at the time of this writing. In addition to other symptoms, the brain disorder commonly robs patients of their personal memories.

Jackson himself commented on the fragility of memory when discussing his election to the Hall of Fame.

“The longer you’re out, the more time they have to forget, and I’ve been out for a long time,” he said in a quote featured in The Hall: A Celebration of Baseball’s Greats.

Fortunately for Jackson, individuals and organizations from across the United States are working to preserve the memories of his life and career. On top of the efforts of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in New York and SABR’s Greg Erion in California, local historians such as Jim Yeager are doing their part to keep the Waldo native’s story alive in his home state of Arkansas.

Yeager, a resident of Russellville, is a baseball historian and published author who specializes in the game’s history in rural areas of the Natural State. An active member of Arkansas’ Robinson-Kell Chapter of SABR, he also pens articles for First Security Bank’s Only in Arkansas blog. On November 15, Yeager released a new article focusing on Travis Jackson and his improbable matchup against Aaron Ward, a New York Yankee and fellow Ouachita alum, in the 1923 World Series. Jackson also has a full section of his own in Yeager’s newest book, Hard Times and Hardball, which is a self-described “collection of stories about the leagues, teams, and players from a time when baseball was Arkansas’ game.”

For Yeager, an interest in studying Jackson came naturally.

“He’s a mysterious guy,” the baseball historian said of Jackson. ”He was a little bit unexpected from Waldo. Photographs of him look like a country boy. You wouldn’t expect a baseball player from towns [like his] to be an actor or a musician.”

Travis Jackson is one of hundreds of life stories from the early 20th century that Yeager and his fellow SABR members aim to preserve.

“We noticed the lack of written history on Arkansas baseball players prior to World II,” Yeager explained. ”I began telling those stories simply because I liked them, but now my friends and I believe the history these men (and women) are an important part of our Arkansas heritage. These guys not only loved the game but needed the game.”

On the left, Jim Yeager stands with his wife, Susan, at Dickey-Stephens Park in North Little Rock, Arkansas. Yeager, a baseball historian and SABR member, covered Travis Jackson and many more Arkansan ballplayers from the early 20th century in his newest book: Hard Times and Hardball (pictured right). | Photos: Jim Yeager/Chase Hartsell Beyond publications, Jackson’s memory lives on through his family. His daughter, Dorothy Jeanne Fincher (better known as “D.J.” to her friends and family), continued to live in nearby Magnolia, Arkansas, until she passed away in 2021 at the age of 92. According to her obituary in the Magnolia Reporter, D.J. Fincher was a lifelong advocate of education. Like her father, she had an interest in music, and she minored in the subject while majoring in history at the University of Arkansas. After attaining a teaching certificate from Southern Arkansas University (SAU), she taught at the now-defunct Waldo School District and, alongside husband Harold, “provided scholarships for many local students to attain a higher education at [SAU].” Fincher’s obituary states that “she [left] behind a legacy of a life well-lived, of a loving and devoted family, and the enrichment of all who had the privilege to know her.” Her son, Dr. Clark Fincher, is a retired, award-winning medical doctor based out of Searcy. Both of D.J.’s daughters, Mary Fowler and Betty Harris, serve with Clark on the board of the Magnolia-based Peoples Bank (which was founded by Harold Fincher’s grandfather in 1910). Fowler is the bank’s current CEO.

Information on Travis Jackson’s son, William, is scarce. According to Fowler’s obituary, William resided with his wife, Peggy, in Sandia Park, New Mexico, at the time of his sister’s passing in 2021. Sandia Park is a census-designated place located approximately 25 miles from the heart of the city of Albuquerque.

Finally, Jackson’s memory survives through lingering remnants of his life found in Waldo more than 35 years after his death. Those wishing to pay their respects to the Hall of Famer can still visit his final resting place at Waldo Cemetery. He is buried next to his wife of nearly 60 years, Mary, in a family plot that they share with his parents.

The Jacksons’ white frame house also remains standing at the intersection U.S. Highway 371 and Arkansas Highway 98 in Waldo. For those unacquainted with Travis Jackson and his story, the building may be nothing more than another home in a rural Arkansas town of just over 1,100 people. To those who are familiar with the house’s most famous resident, however, the site serves as a reminder of the fact that an excellent athlete can come from anywhere.

A determined Travis Jackson looks off into the distance. Though Alzheimer’s disease may have taken his life in 1987, his memory lives on through historic preservation, his family, and his hometown of Waldo. | Photo: National Baseball Hall of Fame -

The Coach Behind the Bear: Bill Walton

By Chase Hartsell

The following article is part two of a series titled “Hidden Heroes: An Arkansas Sports Anthology.” The state of Arkansas has a rich athletic history and, as such, has plenty of sports stories to tell. As a result of this plethora, however, some stories have slipped through the cracks. “Hidden Heroes” sheds light on lesser-known, yet valuable sports tales from the Natural State that have received limited coverage either in their own time or in the present day. Furthermore, the series aims to go beneath the surface of featured athletic stories to uncover universal themes and truths that transcend both time and sport. Click here to read part one, which covers Jim and Leander Tugerson’s push for integration with the Hot Springs Bathers in 1953.

A 1981 collectible Coca-Cola bottle honoring Paul “Bear” Bryant sits beside a football bearing the logo of the Ouachita Tigers. While the famous college football coach and a Division II football program in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, appear to have little in common on the surface, they are linked together through one unlikely individual. | Photo: Chase Hartsell This weekend, Ouachita Baptist University’s football team returns home for a game at Cliff Harris Stadium in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, after back-to-back weeks on the road. The Tigers (5-1), led by head coach Todd Knight, are currently defending their 2022 Great American Conference (GAC) championship after going undefeated in the regular season a year ago.

Knight, a winner of six GAC titles and Coach of the Year awards, is the latest in an esteemed lineage of head coaches for the Tigers. This fraternal group includes the likes of Buddy Benson, a four-time conference champion and the program’s all-time leader in coaching wins. It also features Jimmy “Red” Parker: a coach who spent 50 years leading high school and college programs across the state of Arkansas and the nation.

Only one Ouachita coach, though, can claim that he coached a young Paul “Bear” Bryant. That man is Bill Walton.

Playing Days and Fordyce Football

William “Bill” Walton, not to be confused with the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame member of the same name, was born in Benton, Arkansas in 1900. After starring for Benton High School’s team and winning a state championship in 1918, he continued his playing career with Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas. Walton’s stint with the Warriors lasted just one season, and he soon moved on to the Ouachita Tigers. Despite being known for his play at defensive end in high school, the young man from central Arkansas found himself frequenting the halfback position in college. After playing for four years under Coach Morley Jennings (who ranks third on Ouachita’s all-time win list behind Benson and Knight), Walton set out to start a coaching career of his own.

The first stop on Walton’s coaching journey was Bauxite, Arkansas (which is just minutes away from Walton’s hometown of Benton). In 1924, he received and accepted an offer from Fordyce High School in Fordyce, Arkansas.

Fordyce is the seat of Dallas County and, according to U.S. Census records, saw its population peak just shy of 5,200 in the 1980s. In pop culture, the town is famous for hosting the arrest of two members of The Rolling Stones on the way to a concert in 1975: an episode retold at the beginning of Keith Richards’ autobiography titled Life. In the sports world, however, eyes often turn toward Fordyce High School’s Redbug football team. According to local records, Walton was the head coach of the program when it gained its unique nickname.

Fordyce’s mascot ties back to an unusual development that occurred during the construction of the school’s football field. As workers (including football players and local community members) tried to clear the land for the stadium, they found themselves being pestered relentlessly by trombicula: known informally as red bugs. Local sportswriter Willard Clary, according to Encyclopedia of Arkansas, suggested Redbugs as the team’s new name. The name stuck. The Redbug Alumni Foundation writes that when construction on the new field came to a close, Fordyce decided to name it Walton Field in Bill’s honor.

After opening his head coaching career with a 6-0 victory over Arkadelphia, Walton received the chance to face his alma mater, Benton, in his second game in 1924. The Redbugs blanked the Panthers in a 12-0 shutout. A week later, Fordyce faced another of its head coach’s former teams in the form of Bauxite. The Miners were no match for the Redbugs, and Coach Walton remained undefeated with a 26-0 win. Fordyce would not allow a single point until its fifth game (a 22-7 victory over DeWitt), with the defense holding opponents to seven points or less in nine of 10 games that season. The lone exception was a 32-0 loss to Pine Bluff: the Redbugs’ only defeat in Walton’s first season. This allowed Fordyce to play with a chip on its shoulder the following week, with the result being a 66-0 blowout of Stephens High School. According to the records of former Redbug and team historian, George A. Rogers, Sr., 66 points in a single game remained a school record more than seven decades later.

Following a year of growing pains in 1925 (2-5-2), Walton and his Redbugs bounced back with a 5-4-1 record in 1926. While Fordyce, in its fourth game of the season, once again bested Benton in a 12-0 victory, the Redbugs’ most compelling contest that year was arguably their first.

Bill Walton retained strong ties with Ouachita and Coach Jennings after his playing days. Hoping to provide his players with valuable experience, he scheduled an exhibition game with reserves from the Tigers’ program, with Rogers, Sr., referring to this squad with the unforgiving name of “Ouachita Scrubs.” The reserve Tigers eked out a 7-6 win over the Redbugs, though they could only manage a 0-0 tie when the teams met again the following season.

Walton coached at Fordyce High School through 1928, accumulating a 26–14-2 record in the process. Though the Redbugs of the 1920s enjoyed many triumphs, they are likely best known for introducing the game of football to a man that would become one of its most influential coaches.

The Birth of the Bear

As the winner of six national championships and 323 games (both records in college football at the time of his retirement), Paul “Bear” Bryant is an individual requiring little introduction. Known for his time as head coach of the Alabama Crimson Tide, his extensive track record of success, and his classic houndstooth hat, Bryant was born just outside of Fordyce in Moro Bottom, Arkansas, in 1913. He began his schooling in the nearby Kingsland community, which later gained fame as the birthplace of country music legend Johnny Cash.

When he was 11, Bryant and his family moved to a home within the Fordyce city limits. One year later, Paul Bryant earned his nickname, “Bear,” when he accepted the challenge of fighting a live bear for one minute on the stage of the local Lyric Theater. The prize if he succeeded? One dollar. Bryant, known for his size and tenacity, completed the minute-long fight but did not receive his reward. The tale of his fight with the bear, however, would stick with him for the rest of his life.

Today, the building that housed Bear’s christening fight remains standing, with the Benton Hardware store serving as its most recent resident. A Dallas County Museum plaque near the structure’s storefront on Main Street proudly declares the location the “Site of the LYRIC THEATER, where PAUL WILLIAM ‘BEAR’ BRYANT earned his famous nickname in 1927.” An additional banner hangs above a back counter in the modern store layout, designating it as the former site of the Lyric Theater stage: the exact location where the fight took place. It features caricatures of a bear and Bryant himself, with text reading in all caps: “PAUL ‘BEAR’ BRYANT WRESTLED THE BEAR HERE.”

A Local Legend and Historical Puzzle

Another influential story from Bear’s time in Fordyce is his introduction to the game of football. According to the legend, which has been documented in numerous biographies such as Keith Dunnavant’s Coach and S.C. Lee’s Young Bear, a 13-year-old Bear Bryant walked by Walton Field (now known as Paul “Bear” Bryant Stadium) as the high school team conducted practice. While he watched, a coach noticed him and his remarkable size. This coach walked over to Bryant and asked him if he would like to play football. The young man replied that he would like to play, but he didn’t know how. This question led to Bear’s first football lesson and, the following Friday, Bryant took the field with the Redbugs for the first time.

The identity of this influential coach remains unclear even today. Dunnavant’s biography suggests that the mystery coach was Bob Cowan, who led the Redbugs to an undefeated season and state championship as head coach in 1929. Lee’s Young Bear does not actively dispute this claim but omits the coach’s name altogether.

Writer Jennifer Horne, however, believes that this coach could have been her grandfather, Bill Walton. Horne, the poet laureate of Alabama from 2017 to 2021, revealed in a 2014 blog post that a cousin told her that “[her] grandfather was Bear Bryant’s first coach in Fordyce, Arkansas.” She conducted follow-up research and found that the years of Walton’s coaching stint at Fordyce matched up with Bryant’s junior high years. An organizer of the Dallas County Sports Hall of Fame also wrote Horne, stating that the organization “determined that Bill Walton did indeed coach Paul ‘Bear’ Bryant on the Fordyce Redbug football team.” The organizer went on to explain that “Bryant was rather large for his age, so as a ninth grader, he played on the senior high team, which was coached by Coach Walton.” Nonetheless, Horne noted that “the Bryant biographies [she’s] seen don’t mention [her] grandfather,” though she is “not sure why.”

Multiple Bear Bryant biographies, including those by S.C. Lee and Keith Dunnavant (pictured left), have addressed Bear’s introduction to football. Among these sources, there is a lack of consensus on the identity of the coach that taught Bryant how to play the game in Fordyce. Former Alabama Poet Laureate Jennifer Horne (pictured right) believes that this mystery coach may be none other than her grandfather: Bill Walton. | Photos: Chase Hartsell/Poetry Foundation One contributing factor to this confusion could be the lack of clarity surrounding Walton’s departure from Fordyce. While the collection of Rogers, Sr., credits Walton with the team’s results in 1928, he is noticeably absent from the team’s composite for the season (which was the first to feature Bryant as a Redbug). Coach Bob Cowan, Walton’s eventual replacement, does appear in the 1928 composite, but there is no decisive evidence or labeling to suggest that he served as the team’s head coach that year.

While the debate on who taught Bear to play football continues on, scholars agree that Bill Walton was the head man at Fordyce when the young Bryant first played for Fordyce in 1927. Though exact dates are unclear, multiple reports indicate that Walton took over the head coaching position at El Dorado after leaving the Redbugs. During his six years with the Wildcats, Walton led El Dorado to a 51-9-4 record and back-to-back state titles in 1932 and 1933. According to a 2018 article by the El Dorado News-Times, Walton’s win percentage remains the highest-ever by an El Dorado head coach.

A Call Home and a Call to Service

In 1934, Walton returned to his collegiate alma mater as the head coach of the Ouachita Tigers. Under his leadership, the team compiled a 49-30 record in nine seasons and won an Arkansas Intercollegiate Conference Championship in 1941. In 1942, the coach concluded his tenure with the Tigers in dominant fashion with back-to-back lopsided wins over Louisiana Monroe (62-0) and Peru State (64-0) in his final two games. The Tigers canceled their next two seasons due to World War II.

Bill Walton did not return to coach the Tigers, though Jennifer Horne believes that he could have. In the aforementioned 2014 post, she referenced Walton’s obituary, recounting a story where a Ouachita president explained that “if Coach Walton had waited to be called up [for the military], he could have saved his position.” Instead, “the coach decided to enlist, knowing his job would not be there when he returned.” Walton joined the United States Navy, where he rose to the rank of lieutenant commander. After the conclusion of World War II, he returned to Arkadelphia, where he served as an insurance salesman in the community and continued to be “a huge booster” for Ouachita until his death in 1963.

A mature, focused Bill Walton gazes just off camera in a photo from his time as head coach of the Tigers. Walton returned to Ouachita in 1934 after a successful run as a high school coach from 1924 to 1933. | Photo: Ouachita Athletics A Lasting Legacy

Throughout his career in football, Bill Walton earned respect from coaches across the southern United States. According to Horne, Bear Bryant, Arkansas Razorback legend Frank Broyles, and other football royalty paid their respects to Walton at his funeral.

Years after his death, appreciation of Walton’s work continued through local sports halls of fame. In 1973, he received a posthumous induction into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame for his time coaching Arkansas high school programs and the Ouachita Tigers.

Thirty-five years later, Walton received entry into the Ouachita Athletic Hall of Fame. Today, his portrait hangs alongside those of other inductees on the wall of the university’s Sturgis Physical Education Center (known by the acronym SPEC). The university also honored the coach with Bill Walton Gymnasium, a former athletic facility that stood “on the northwest corner of campus.” Originally housing varsity basketball games on campus, Walton Gymnasium also, according to a school handbook from the 1963-64 school year, “serve[d] as the center of the Physical Education department and the School of Military Science” at Ouachita. In her thesis for OBU’s Carl Goodson Honors Program, Victoria Utterback reports that the site continued to house women’s basketball practices and intramural events even after the construction of newer buildings such as Winthrop Rockefeller Field House in 1966 and SPEC in 1983. Ouachita demolished Walton Gymnasium in 1985 to make room for new projects. Utterback writes, “While the students would miss the old gym, they welcomed the new changes.”

An aerial shot of Ouachita’s former campus layout features Walton Gymnasium (circled, top left). The facility, named in Bill’s honor, served as the home of basketball games, team practices, and intramural events before being demolished in 1985. | Photo: Ouachita Baptist University Finally, in 2014, the Dallas County Sports Hall of Fame added Bill Walton to its ranks. Members of the group are honored in a photo gallery on the second floor of the Dallas County Sports Museum, which is located in the Bill Mays Annex of the Dallas County Museum in Fordyce.

“We have quite a sports history,” said Dallas County Museum staff member and Fordyce resident Melrose Bagwell.

The museum seeks to preserve said history through the Dallas County Sports Hall of Fame gallery (which also includes “Red” Parker and Bear Bryant himself, among others) as well a lower floor of exhibits that showcase the rich tradition of the Redbug football program and other notable teams and athletes in the county. A highlight is the football collection of 1949 Fordyce graduate George A. Rogers, Sr., which features materials on Bill Walton and fellow Redbugs that range from 1909 to the early 2000s.

In the back of a binder featured in the collection, Rogers writes, “There is no such thing as a complete history of anything, especially something as rich in tradition as Fordyce Redbug Football.” Perhaps the same can be said of Bill Walton himself: a coach who, in spite of his achievements, remains shrouded in mystery. Regardless, his name will be forever linked with Fordyce’s eight-time state champion football program. It will also be tied to a certain man from Moro Bottom, who discovered and learned to love the game of football under Walton’s Redbug regime.

Bill Walton’s portrait hangs proudly as a part of the Dallas County Sports Hall of Fame gallery on the second floor of the Bill Mays Annex of the Dallas County Museum. Walton joined the Dallas County Sports Hall of Fame as a part of its 2014 class. | Photo: Chase Hartsell/Dallas County Museum Visitors can access the Bill Mays Annex upon request during Dallas County Museum hours. Admission to all of the museum’s exhibits is free, though the facility’s website ensures guests that “donations are welcomed and appreciated.”

On Saturday, October 21, Ouachita will celebrate all of its previous football team members with Football Alumni Day at Cliff Harris Stadium. That day, the Tigers will take on Great American Conference foe Arkansas Tech at 1 p.m.

Six days later, the Fordyce and Arkadelphia football communities will cross paths when the Redbugs host the Arkadelphia High School Badgers for a non conference bout. The game will take place at Paul “Bear” Bryant Stadium in Fordyce on Friday, October 27, with kickoff being slated for 7:00 p.m.

-

Hot Springs’ Hidden Heroes: Jim and Leander Tugerson

By Chase Hartsell

In 1953, Jim (pictured left) and Leander Tugerson (pictured right) attempted to integrate the still-segregated Cotton States League with the Hot Springs Bathers. | Photo: Polk County History Center As the birthplace of professional baseball’s spring training tradition, Hot Springs, Arkansas, is no stranger to the history of America’s pastime. Any town that has hosted the likes of National Baseball Hall of Fame members Babe Ruth, Cy Young, Jackie Robinson, and Henry “Hank” Aaron is sure to have its fair share of stories. Even still, some stories and hidden heroes of the game’s history in the Spa City have slipped through the cracks.

Most baseball fans are likely familiar with the fact that, in 1947, Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier. What may go unrealized, though, is that some minor leagues required pioneers similar to Robinson even years later.

One such league was the Cotton States League (CSL), an organization of minor league clubs across the states of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana. As the 1953 season approached, the CSL had yet to be integrated. One member team based out of Hot Springs looked to change that.

On April 1, 1953, the Hot Springs Bathers signed brothers Jim and Leander Tugerson. The sibling pitchers were from the Polk County community of Winter Haven, Florida, which, in modern times, is approximately an hour by car east of the city of Tampa. In 1952, the two threw for the Indianapolis Clowns: baseball’s answer to the Harlem Globetrotters at the time. With Jim and Leander in their rotation, the Clowns brought home a Negro American League title. That championship team also featured a young Henry “Hank” Aaron, who spent time as Jim’s roommate over the course of the season.

As a minor league rooted in a southern United States still ruled by the laws of Jim Crow, there was, expectedly, opposition amongst CSL members. Even when the Bathers revealed their plans to throw the Tugersons only in home games at Jaycee Park, other CSL team owners felt the limitation on the two brothers’ participation in the league was not enough. As a result, on April 6, 1953, they voted 6-0 to expel the Bathers from the league. The Hot Springs club, led by team president Lewis Goltz, continued to stand by its new players.

Just nine days after the vote, the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues overruled the CSL’s decision and reinstated the Bathers. The team did not take the field with its new signees, though, as Jim and Leander Tugerson would be sent to Tennessee to play out the season with the Knoxville Smokies (known today as the Tennessee Smokies, the Double-A affiliate of the Chicago Cubs).

Hot Springs, however, did not give up on bringing the Tugersons to Jaycee Park. JET Magazine reports indicate that, as early as May 7, Lewis Goltz “warned officials that the Tugersons would be back [the] next year, if not [that] season.” Less than two weeks later, Goltz followed through on this promise.

On May 20, the Bathers called Jim Tugerson back to the Spa City for a start against CSL foe Jackson. Tugerson’s start served as a highly-anticipated event in the community, and 1,500 fans flocked to Hot Springs’ home field to witness the right-hander’s long-awaited debut with the Bathers. That debut never came to pass.

Jim Tugerson (center), set to make his Bathers debut vs. Jackson on May 20, 1953, stands by teammates as he receives the news that Hot Springs must forfeit moments before the game’s first pitch. | Photo: JET Magazine/Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia Before a pitch could be thrown, CSL president Al Haraway, who had opposed the Tugersons’ participation in his league from the start, declared that Hot Springs must forfeit the contest. While an article published in Jackson’s own Clarion-Ledger the following day suggests that Hot Springs did not take immediate action in regards to Jim’s roster status, JET writes that, by early June, Lewis Goltz had “returned Tugerson to Knoxville, promis[ing] not to recall him.”

While neither group achieved the integration they longed for in 1953, the Tugersons and the Bathers did witness positives in the year to come. Though Leander’s work that season was limited by an arm injury, Jim led the Smokies’ Mountain States League (MSL) with 29 wins on the season. He proved to be the team’s ace in a memorable run to the 1953 MSL title. Hot Springs, just one year removed from a 43-83 campaign, posted a 63-61 record in 1953. The club forced a one-game playoff with Jackson for fourth place in the Cotton States League, but fell just short to cement a fifth-place finish.

Before the year ended, Jim attempted to sue the CSL for barring him from playing for Hot Springs. According to an article published in JET on September 24, 1953, “Federal Judge John E. Miller denied that the Cotton States League violated pitcher Jim Tugerson’s civil rights when it refused to the let him play” because the party denying his entry consisted of “private organizations and individuals.” Nonetheless, Jim finally received the opportunity to pitch at Jaycee Park during a barnstorming exhibition against his former team, the Indianapolis Clowns, in September. Tugerson put on a dominant performance, leading his squad to a 14-1 victory.

In 1954, Hot Springs achieved its goal of integrating the CSL. On July 20 of that year, Uvoyd Reynolds, a recent graduate from local Langston High School, debuted with the Bathers as the first African-American ballplayer in league history. While his professional career lasted only five games, the Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail honored Reynolds by including his name on a plaque of notable figures that participated in the Spa City’s baseball tradition. Jim and Leander Tugerson also received a tribute on the sign, though they are collectively listed as “The Tugerson Brothers” without mention of their first names. This marker can be found in three locations: the first is located near the Arkansas Alligator Farm and Petting Zoo, which sits across the road from the former location of Whittington Park on Whittington Avenue. Identical markers are placed in front of the entrance to Oaklawn Park Racetrack and near the Hot Springs Visitor Center, respectively, on Central Avenue.

Uvoyd Reynolds (pictured left) officially integrated the Cotton States League with the Hot Springs Bathers in 1954. Both he and the Tugerson Brothers are recognized as notable figures on a Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail plaque (pictured right) that can be found at multiple locations throughout the city. | Photos: Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia & Chase Hartsell After his injury-shortened 1953 campaign, Leander Tugerson retired from professional baseball. For Jim Tugerson, however, 1953 marked the beginning of a successful career in the minor leagues. While he never reached the major leagues, Tugerson continued to pitch for an additional five seasons and even made it to Triple-A with the Dallas Rangers of the American Association in 1959. He finished with 86 wins and over 1,000 strikeouts in six seasons of minor league ball.

In 1965, Leander Tugerson passed away in his native state of Florida just four days after turning 38 years old. His older brother, Jim, would outlive him by 18 years. According to his biography by Society of American Baseball Research historian Peter Morris, Jim returned to Winter Haven and served as a police officer there for over 25 years, going on to reach the rank of lieutenant. He also remained involved in baseball by serving as a youth coach in the area. Morris writes that as he coached a game exactly one month after turning 60, Jim Tugerson experienced a life-ending heart attack in 1983. Inspired by his service to the Winter Haven community, the city council voted to rename a local baseball field in his honor. To this day, Tugerson Field stands as a tribute to the baseball pioneer, who continued to leave a positive impact even after his days on the mound concluded.

“The City of Winter Haven is very proud of the legacy Jim and Leander created,” said Jayme Jamison, who serves as as a curator of education and visitor engagement at the Polk County History Center in Bartow, Florida.

Jamison explained that, while the Polk County History Center does not currently have access to any archival items related to the Tugersons, the facility has “done a bit of work correlating some secondary sources and creating general descriptions for [its] exhibitions and features” concerning the brothers. In 2022, Polk Government Television, which broadcasts via regional cable and online platforms, created an informational segment about the Tugersons as a part of its Black History Month program. The segment is available to watch now on the Polk Government channel on YouTube.

Back in Hot Springs, Jaycee Park was eventually absorbed into the local Boys & Girls Club, which closed in 2018. The facility was later demolished to make way for the Majestic Park baseball and softball complex that opened in 2022. Today, Majestic Park encourages young men and women of all backgrounds to play ball on the same site where the Tugerson brothers attempted to integrate the CSL 70 years ago. The Natural State Collegiate League (NCSL), which began in 2022 and plays its games at Majestic, paid tribute to Hot Springs’ historic minor league club by making the Bathers one of its four founding teams. In 2023, after finishing the regular season in sixth place and losing their first playoff game, the Bathers rallied with three straight wins to claim their first NSCL championship.

For more information on the history of the Hot Springs Bathers, check out Don Duren’s book Bathers Baseball. To learn more about Jim’s momentous 1953 season, look into R.S. Allen’s biography Schoolboy: Jim Tugerson: Ace of the ’53 Smokies.

The preceding article is dedicated to Mike Dugan (1954-2021). Dugan was a native of Hot Springs and, as a small child, attended Bathers games during the team’s final seasons. A lifelong baseball fan, he later served as a leading curator for the Hot Springs Historic Baseball Trail and a board member at the Hot Springs Boys & Girls Club. In his final years, Dugan was a driving force in the city’s “Home Run for Hot Springs” campaign, which led to the construction of the Majestic Park complex. Dugan Plaza, the hub of the Majestic facility, is named in his honor. Dugan would have turned 69 on July 17.

-

Marceline Magic: How my sister’s art in a small, northern Missouri barn appeared in an official Disney film

By Chase Hartsell